A British diplomat and French diplomat exerted their influence during the last tumultuous days of the Tokugawa Shogunate, but with different goals.

(Posted on August 20, 2025)

As is well known the Tokugawa Shogunate opened its doors to the west in 1854 after nearly three centuries of self-isolation. So, western countries dispatched their diplomatic missions to Japan. Their first priority was to establish the terms of trade and commerce. What was Japan like at that time, a peaceful and cooperating country? Not in the least. History tells us that this opening met strong opposition in Japan that actually led to the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate merely 14 years on.

Why was there opposition to the doors opening? First and foremost, it caused a wave of shock and fear when “gun boat diplomacy” was orchestrated by Mathew Perry, who led the US Navy steam vessels to Japan intending to force open its doors, first in 1853 and the year later to finalize a treaty. It’s important to note that the story of the Opium War (1840-1842) in China was well known in Japan. So, the Tokugawa Shogunate was criticized for being compelled to sign the treaty, without asking for the emperor’s approval.

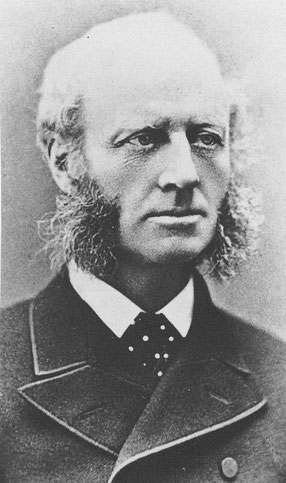

With this background, even though risk existed to their own lives at the hands of fanatics, western diplomatic missions were sent representing their countries. Here, we would like to focus on two diplomats who played important missions, but with different goals. First comes Harry Smith Parkes (1828-1885), who was a British minister from 1865 to 1883.

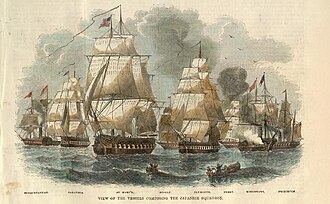

Parks was a seasoned diplomat in China serving as a minister in Shanghai before coming to Japan. He was fluent in Mandarin because of his upbringing (he went to China from Britain at the age of 13 to seek refuge from one of his family members). Parks succeeded his predecessor John Alcock in 1865. Alcock was the first British minister in Japan from 1859-1865. He was also a veteran diplomat in China. Alcock was actually replaced because of his hawkish stance against the Shogunate and in particular the Choshu clan who fired upon western vessels sailing near its coast. Alcock organized and carried out a four -nations retaliation bombardment against Choshu in 1864 and again in 1865, against the wishes of his superiors at home. It was obvious that Britain’s diplomatic priority in Asia was by far India and next came probably China. So, they were not interested in any military confrontation with Japan.

It's interesting to note that powerful clans, especially Choshu and Satsuma, had been die-hard anti-west clans, but after experiencing battles with the western powers they made a dramatic turnabout without hesitation. It must be mentioned that there was a battle between the British vessels and Satsuma gun batteries in 1863. Both clans decided to adopt western technology, especially military ones.

Here, a British diplomatic mission including Earnest Satoh, who had a deep understanding of Japanese culture and its people, played an important role in bridging Britain and the clans. Actually, twelve young Satsuma Samurai were sent to Britain in 1865 to study at the University of London. They happened to join with other representatives from Choshu. Needless to say, they played important roles in the early Meiji Period.

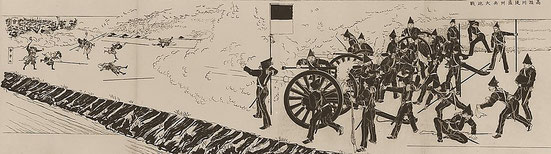

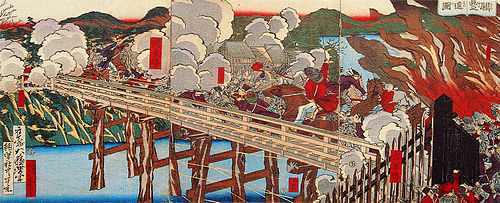

As political tensions intensified in Japan, a series of battles began between forces loyal to the emperor mainly headed by Satsuma and Choshu, and the Shogunate in 1868. In the end, the emperor’s army prevailed and the reign of the Meiji emperor commenced thereafter (1868-1912).

Parkes remained neutral during the battles in accordance with the strict instructions by the home government relating to any foreign civil wars.

But perhaps because of his deeper understanding of Satsuma and Choshu, Parkes happened to be the first westerner to approve the new government in 1868. Parke’s tenure lasted until 1883, when he was transferred to China as Shanghai’s British minister one more time. During his last days in Japan, Parkes helped and coordinated with the Japanese government for the westernization of the country, and strengthening of the relationship between the two countries.

Now, let’s turn to the French representative, Leon Roches (1809-1900), whose stint as minster lasted four years from 1864 to 1868. Roches succeeded his predecessor, Gustave Bellecourt, who was the first representative of France as Consul General and later became a minister. Like the first British representative, Alcock, Bellecourt took a strong stance against the Shogunate that was not appreciated at home as they had more urgent diplomatic issues elsewhere.

Unlike his predecessor and in this instance, also the British minister, Parkes, Roches did not serve in China. Interestingly, he was fluent in Arabic and had served as Consul General in several Arabic countries before coming to Japan. Roches is remembered in Japan as a strong supporter of the Shogunate.

In response to the requests of the Shogunate, which was desperate to modernize its military and industries, France responded. For instance, France assisted to build an ironwork and shipyard (remains today in Yokosuka); a military mission was sent; a French language institute was set up in 1865; a US$ 600 million loan was carried out. On the other hand, there was a request from France to the Shogunate to attend the Paris Expo in 1867. To this, the shogunate responded by sending a Japanese mission headed by the Shogun’s brother. One member of the mission was Shibusawa Eiichi, the father of modern Japanese capitalism.

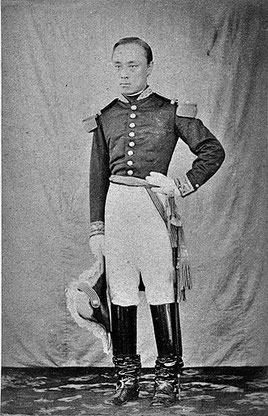

Tokugawa Yosinobu, the last shogun in French military uniform,

which was offered to him by Napoleon III, who also donated 3,000

“Chassepot” bolt action rifles.

When the war started between the forces loyal to the emperor and the Shogunate in 1868, Roches remained adamant to support the Shogun. Incidentally, some French officers of the French military mission joined the shogunate’s army to the end in Hokkaido. When the war ended with the Shogunate’s defeat, Roches was relieved of his stint. He was criticized at home as taking a stance that supported the shogunate. Roches returned to France and retired without ever taking up any further diplomatic stints. Incidentally, two years after the fall of Tokugawa Yoshinobu, Napoleon III abdicated as a result of being defeated by the Prussians in 1870.

From northern Yokohama,

Japan

From northern Yokohama,

Japan